Capital

City Arts Initiative

The

Carson City | Carson Valley Portrait Project: Exploring Community

essay by Marcia

Tanner

|

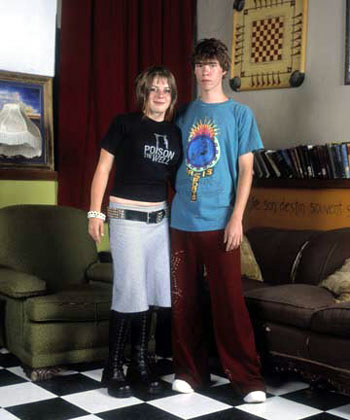

Spore’s approach to portrait making is deceptively

simple. He asks his subjects to pose neutrally, as though they are

having a casual conversation. “I give little direction,” he

says, “but I try to avoid the smiling ’snapshot’.” He

centers the subjects in the frame and prints the images the “contexts” are

lively: the café’s funky jumbled interior, the bare

wall and patterned carpet in an upstairs hotel room at J.T.’s.

Spore is acutely aware of the long, rich tradition of portrait

photography as an art form, and has thoughtfully considered his

place within it. Unlike celebrity

portrait photographers such as Richard Avedon and Annie Liebowitz, he tries,

as much as possible, to be invisible in his work. He wants the subject of the

portrait to be the subject. His model and inspiration is Michael Disfarmer,

a commercial photographer working in rural Arkansas in the mid-20th

Century who

made hundreds of family portraits of ordinary working people. In the 1970’s,

Disfarmer’s images were discovered and later collected in book form.

"When I first viewed the book of Disfarmer portraits I was immediately

drawn to the simple, straightforward, evenly lit style," Spore says. "There

was no 'artistic interference' between

me the viewer and the people he photographed. [I had] a profound sense of privilege

-- a sense of being allowed access to a private and real person. Disfarmer’s

subjects dressed simply and presented themselves . . . without pretense. There

was an honesty and directness that I found compelling and in stark contrast

to our contemporary world of advertising and fashion." [2]

Whether or not it is possible, let alone desirable, for an artist to be totally

objective and entirely self-effacing is open to discussion. The medium of photography

lends itself to such questions more than others, because it is supposedly the

medium of “truth” -- although that notion has been so thoroughly

challenged as to be discredited in recent years, especially since the advent

of digitally manipulated photographic images.

Even without that technology, the claim that photography can present unvarnished

reality is debatable. There is always someone, an actual person, behind the

camera, who is making choices about what will be seen in the photographic image.

This

is especially the case when that person is an artist. Spore might aim toward

a factual way of representing what he sees, but there is a thrilling creative

tension between detachment and commitment in his work. Underneath the cool,

apparently unemotional presentation of his portraits is a highly subjective

vision and a

passionate interest in the subjects he depicts. Why would we look at them otherwise?

He admits as much:

"I am interested in exploring -- and having the viewer explore -- questions

of community. Even in this age of television and our heavily mediated society,

we

each live in a unique community. What does it mean to have large-scale portraits

of people in a community displayed in a gallery exhibition? What is the artistic

experience? I hope the images will stir up questions about personal decisions. “Why

do I live here? Do I feel part of or estranged from these people? How do people

create a community? How do people define community? What are our shared values?

How do we approach diversity?” These are all important questions in examining

our experiences and ourselves." [3]

Beyond these questions is the inescapable fact that you are looking at portraits

of real people who were photographed in a real place in real time, not so long

ago on the streets where you live. Whether you know them or not, your encounter

with their images here and now may make you see them in a new way, may create

an emotional bond between you and them, may even pierce your heart.

Marcia Tanner

Berkeley, California

February 2004

2 Email

from the artist, January 26, 2004.

3 Ibid.

Recommended Reading

Carol Squiers, Christopher Phillips, Brian Wallis, Edward W. Earle,

et. al., Strangers: The First ICP Triennial of Photography

and Video, New York, NY and Steidl, Gottingen, International Center

of Photography, 2002-2003.

Julia Scully, Disfarmer, Heber Springs Portraits 1939-1946, Santa Fe, New Mexico: Twin Palms Publishers, 1996.

Max

Kozloff, Lone Visions - Crowded

Frames:

Essays on Photography, Albuquerque,

New Mexico:

University of New Mexico Press, 1994.

Richard

Bolton, Editor, The Contest

of Meaning:

Critical Histories of Photography,Cambridge,

Mass:

MIT Press, 1989.

Liz

Wells, Editor, The Photography

Reader,

London

and New York: Routledge, 2003

Capital City Arts Initiative