|

Merrilee

Hortt

Small Vanities: Works on Paper 1997 – 2004

Carson City Courthouse Gallery

February 17 – May 23, 2005

. . .

The Attentive Art of Merrilee Hortt

Essay

by Gregrory Crosby

Curators’ note: In conjunction with “Merrilee Hortt: Small

Vanities,” the Capital City Arts Initiative is delighted to present

the essay below by Gregory Crosby. Mr. Crosby is an arts writer and cultural

critic, currently living in New York City. His writing for a broad range

of Las Vegas publications has been instrumental in helping fuel and promote

the cultural renaissance of what locals in the Las Vegas art scene have

appropriately dubbed “The Radiant City”. Our thanks go to

Mr. Crosby for his contribution to “Small Vanities”.

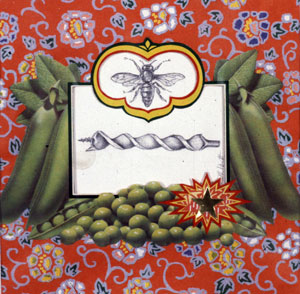

The stormy head of the Bride of Frankenstein hovers above a small group

of zebras on the move, like a weird Gothic cloud above the veldt. “Winged

Victory” stands in its headless splendor while regarded by a flamingo,

a crane, a seagull. Tiny clowns take pratfalls before a towering ridge

of beer bottles. Three twisting candles hold themselves upright casting

long shadows in search of a birthday cake. Lips align themselves with

a wood screw, or a contortionist aligns himself with a pair of scissors,

or a bullfrog with a revolver, each in an elaborate patterned proscenium

of peach halves or string beans. It must mean something—literally

so in the case of the latter images, dubbed “It Must Mean Something

(Gun)” or “It Must Mean Something (Profile).” And

it does: it means that someone is paying attention.

That’s what artists do, of course, a faculty so obvious as to seem

almost counter-intuitive. When much of contemporary art seems mired in

a deliberate vagueness—casual, glancing, insipid in either concept

or execution—it’s the artist who simply finds the salient

or unexpected detail and vividly renders it that most captures our own

attention. The artist who makes grand gestures out of very small ones,

and does it without ever seeming grand herself. Having experienced Merrilee

Hortt’s works on paper for over a decade, I’m always simultaneously

surprised and knowingly satisfied by her attentiveness, and the skill

with which she transmutes it into pictures that are rich, complex and

mysterious without ever becoming unnecessarily showy or cheaply shocking.

The kind of shock Hortt trades in is a quiet one: the shock of recognition,

coupled with a split-second sense that you have no idea what you’re

looking at, even though the object is clearly a fork, its twines casting

sinister (why sinister?) shadows. In her “Small Vanities” series

of drawings, each object—a rose, a bicycle horn, a swatch of fabric—is

both itself and something more. Somehow Hortt captures the varied associations,

emotional and rhetorical, that abound in everyday things. We would see

these associations bubble up into our minds constantly, if we ever stopped

long enough to regard a pair of salt and pepper shakers or a fortune

cookie the way Merrilee Hortt does. We would revel for a moment in our

inescapable materialism—our attachments to the little things that

make the world not just easier or better, but in a sense possible. The

cliché claims its no good to be hung up on mere things, but

things are the pegs we hang our bodies and senses on: the physical

world that

without which a spiritual dimension would be meaningless.

Hortt is well attuned to this, and deftly re-focuses the viewer’s

attention on the connections between the world around us and ourselves,

connections that are so matter-of-course they might as well be breathing.

And like breathing, which becomes quietly miraculous when you pause and

focus on your own lungs, expanding and contracting, Hortt makes little

miracles out of juxtapositions of sight and sensation, as in “Self

Portrait as a Teal Dress” and “Self Portrait as a Blue Dress.” Here,

Merrilee Hortt pulls and squeezes her own face until it resembles the

folds in fabric: flesh becomes fashion and vice versa. Or she draws attention

to language and its intentions and representations: in “Handout/Hand

Out” a mottled old hand extends as if in greeting above the stylized

hand of a palmistry map. In one of her most strangely poignant and funny

images, “A Marriage,” white elephants waltz in awkward embraces

in the foreground while a still life of varied candles in elaborate holders

loom above them in the darkness. The image is packed with so many intimations

of marriage’s mortality and endurance: its memories and brief

flickering loves and desires, and its absurdities.

It’s important to note another obvious factor in Hortt’s

ability to so vigorously communicate her deep attentiveness: she can

draw like the devil. Her work, rendered in graphite and gouache, in silverpoint

and pastel, is sharply observed yet delicately shaded and full of nuance.

She seems less interested in line than in form, but it’s with form—with

her ability to make objects present and shadowy at the same time—that

she is able to draw the reader into the picture. A bold graphic design

sense would merely realistically represent, say, that thumbtack or drill

bit without evoking the associations that are contained in “thumbtack” or

a “drill bit.”

There’s something deceptively simple in Hortt’s ability to

remake and re-engage the world with simply a pencil and a few objects.

It seems so effortless, but don’t be fooled. There’s nothing

harder—or more essential—for an artist than to simply pay

attention. Merrilee Hortt’s drawings perfectly demonstrate the

rewards—for herself, and for the viewer—that such attention

pays.

Gregory Crosby

New York, New York

February 2005

.